The three lectures were held on Monday afternoons in October in Leuven. And the lecturer Magda Michielsens explained why these writers were considered to be Unvictorian.

In the Victorian era, women in general were expected to either get married and raise a family (and support their husbands) or, if they did not marry, find a job as a governess (middle class) or in a factory or in service (lower class). All the women in the title did not follow that Victorian pattern. They did not conform to the Victorian model of living, the Victorian ideas of how women should behave, act, live their lives – they all became famous writers in their own right and claimed their place in literature.

The three Brontë sisters – Charlotte (1816-1855), Emily (1818-1848) and Anne (1820-1849) – were first in line in the lectures. Of course, being a Brontëite I did not expect to learn much from this talk on the Brontë family. But I was curious to see how this vast subject would be handled in this series of lectures. The approach and the focus were somewhat different than what I would have chosen. The lecturer sometimes went into extreme detail on some minor aspects of the Brontë family biography while not focussing on other major aspects of their lives.

On the first Monday afternoon, the family history in general was dealt with (parents’ background, move to Haworth, education, childhood years, death of mother and two siblings, Brussels, publications under male pseudonyms – Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell – further deaths in the family, Charlotte left alone, marriage, Charlotte’s death, her legacy). A lot of focus went on Charlotte Brontë and her novels: the refusals she received from publishers for her first novel The Professor, detailed explanation of Jane Eyre (and a reference to the prequel Wide Sargasso Sea by Jean Rhys – the lecturer obviously admired this book), a brief explanation of Villette (and a reference to Jolien Janzing’s novel De meester / Charlotte Brontë's Secret Love).

Due to the lack of time, the lecturer explained that Emily Brontë and her work would not be dealt with in detail, which I personally found very regrettable and disappointing as Emily in my view is the greatest poet ever and Wuthering Heights is a real masterpiece. But I may be biased!

On the other hand, Anne Brontë and her two novels (Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall) were extensively dealt with on the second Monday afternoon (first half). Michielsens clearly is a fan of Anne’s work. I was glad that Anne also received some credit, for she has been in the shadow of her siblings for far too long. Anne was the only one of the Brontës who was able to hold on to her job as governess (unlike her sisters who hated the work). Special (though brief) attention was also given to their brother Branwell and to the curate William Weightman, because both these men had an influence on Anne’s novels and her poetry. Anne was definitely ahead of her time in dealing with questions regarding domestic violence, feminism, independence of women, the role of women in society, etc.

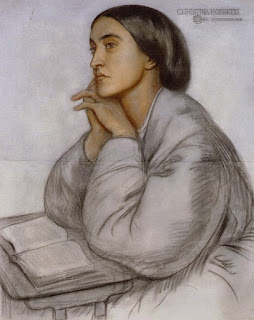

The second half of the session was dedicated to the Rossetti family with special attention to the poet Christina Rossetti (1830-1894).

|

| Christina Rossetti |

Christina was placed among the four best female poets of the Victorian era (the others being Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Emily Brontë and Emily Dickinson). She wrote many religious poems, some love sonnets and some children’s poetry. Her family was well known in the cultural and art world of the time. Her brothers were involved in the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. She posed for portraits by her brother Dante Gabriel many times. She was ill most of her life, but this did not stop her from writing poems and becoming very successful during her lifetime.

She was a recluse (she lived with her mother), although she kept a wide circle of friends and correspondents. She had three suitors and offers of marriage, but she declined them all for religious reasons. But she wrote some beautiful love sonnets. Her religion was very important to her throughout her life, and ”death and loss” as a theme was central in many of her poems. But some of her work can also be seen as a critical comment on gender roles in the Victorian era, which was also very unconventional.

The third Monday afternoon was dedicated entirely to George Eliot (1819-1880). Her real name was Mary Ann Evans. She was a journalist, essayist, editor and translator in her “first” career, publishing a lot of non-fiction work. When she started writing fiction (her “second” career), she took on a male pseudonym, not because she was afraid that her work would not be treated correctly (her being a woman), but because she did not want her novels to be associated with the “chick lit” books or “pulp literature” of the time (“silly novels by lady novelists,” as she called them). She wanted to be taken seriously.

|

| George Eliot |

Virginia Woolf formulated it as follows: “It may have been not only with a view of obtaining impartial criticism that George Eliot (and also the Brontës) obtained male pseudonyms, but in order to free their own consciousness as they wrote from the tyranny of what was expected from their sex.”

George Eliot met George Henry Lewes (a fellow journalist, philosopher and critic) in 1851 and they fell in love. Lewes was a married man, but he had an “open” marriage. Lewes and Eliot decided to live together as husband and wife, but they never got married officially. Her living with a man out of wedlock was very unconventional in Victorian times and not accepted by Victorian society. Her own family broke all contact with her.

Lewes was the love of her life. He became her manager and agent, protector and proof-reader. Lewes died in 1878, and in 1880 Eliot married a much younger man (John Cross), a decision that was welcomed by some (her brother) and not understood by others. She died in December of the year.

George Eliot was an intellectual, though not coming from an intellectual family environment. As Virginia Woolf described it in May 1921 (Daily Herald): “George Eliot was the granddaughter of a carpenter. She made herself, by sheer determination, one of the most learned women – or men – of her time.” Between 1859 and 1876, she wrote a number of novels (of which Middlemarch is probably the best known one) and became very successful in her own right.

To conclude: The Brontës, Christina Rossetti, George Eliot (and probably many more such as Elizabeth Gaskell) were all female writers living and working under the strict corset of Victorian times, but in their own way they were all breaking with Victorian conventions and became very successful.

In a letter addressed to Charlotte Brontë (on 12th March 1837 – 10 years before Jane Eyre) Robert Southey wrote: “Literature cannot be the business of a woman's life, and it ought not to be. The more she is engaged in her proper duties, the less leisure will she have for it even as an accomplishment and a recreation.” Haven’t all these “un”victorian female writers proven him wrong!

I really enjoyed these lectures and the different approach taken on these female writers. I’m glad I was able to attend and I learned a thing or two along the way. Amarant is an organisation that provides a wide range of cultural activities. I look forward to other similar lectures on their future programme.

-- Marina Saegerman

No comments:

Post a Comment