In his talk on Saturday, 24 February 2024, Johan’s special fake-news focus was the enduring claims that Branwell Brontë must have been the true author of Wuthering Heights. The first serious biography of Emily didn’t come until 1883, when Mary Robinson published her book, so there was plenty of time and scope for speculations.

The fake news was fed early on by the Brontë sisters’ use of pseudonyms – Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell – which led to an air of mystery around the novels and their authors, Johan said. This prompted conjecture about who exactly the Bells were, as well as how many Bells there were.

Contributing to the disinformation around Wuthering Heights and its author was Thomas Cautley Newby, the novel’s first publisher. The unscrupulous Newby promoted Ellis Bell’s book as by the author of Jane Eyre, and he did the same thing later with Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, advertising it as the third novel of Mr. Bell. “So readers had reasons to be puzzled about the number of Bells,” Johan said.

And then there was the gender issue, coupled with the coarseness, violence and depravity depicted in Wuthering Heights. While critics were swept away by Jane Eyre, they didn’t know what to make of Ellis Bell’s book. “Wuthering Heights was a strange novel, full of passion, and more in the German romantic tradition,” Johan said.

|

| 'By the author of Jane Eyre' |

Johan quoted one early critic in an American magazine: “How a human being could have attempted such a book as the present without committing suicide before he had finished a dozen chapters, is a mystery.”

Some critics speculated that Ellis Bell was a woman, but if this novel was indeed the case, it was even more astonishing and require another explanation (like a man – Branwell – really wrote the book). Some critics said such a novel could not be written by a woman – or at least should not. Could such a coarse novel really be written by a shy, unsociable young woman, as Emily was depicted to be?

“The fact that some considered that a masterpiece of violence and immorality could definitely not have been the work of a woman would later be interpreted to Branwell’s advantage,” Johan said. In this viewpoint, the author “simply had to be Branwell.”

The idea that Emily was a shy, unsociable girl was launched by Charlotte herself in 1850 when she published her preface to the second edition of Wuthering Heights. Charlotte tries to soften the charges of coarseness of against the novel by saying that Ellis Bell was living in an isolated place, in a remote district, far from the civilized world, writing about rustic characters encountered in that secluded world.

“Charlotte gives her own personal, censured, even sanitized, version of the Emily we still know today – an unsociable girl living far from civilization, who just noted what she saw around her,” Johan said.

Then Elizabeth Gaskell took that explanation and ran with it in her Life of Charlotte Brontë, published in 1857. “That is why Gaskell depicted Haworth as a forlorn hellhole on the edge of the civilized world, which of course it wasn’t, since Haworth was situated only five miles from Keighley.” More fake news.

Gaskell also emphasized the idea that Branwell was a failed artist and a failed scholar. He was also a failed station master, and an unreliable private teacher, addicted to alcohol, always to be found in the local pub with the wrong friends. And of course an opium eater and gambler. For Gaskell, Branwell is the explanation for the detailed knowledge the Brontë sisters seemed to have of drunkards and gamblers – “they just noted what they saw,” Johan said.

Gaskell aimed to defend Charlotte’s literary reputation, and therefore she downplayed the literary achievements of the other siblings. Gaskell described Emily as crude and reserved.

More fake news came in 1867, when William Deardon, a friend of both Branwell and Rev. Patrick Brontë, wrote a magazine article championing Branwell as the author of Wuthering Heights. He made the point that Charlotte’s 1850 preface was the only concrete claim of Emily’s authorship, and he recalled a scene in the Cross Roads Inn around 1842 when Branwell read out some pages he claimed to have composed that sounded very similar to scenes found later in Wuthering Heights.

Dearden repeats the argument – based on Charlotte’s and Gaskell’s comments – that a young, shy and inexperienced girl could never have conceived such a cruel, coarse and violent novel. Therefore, the novel must have been written, or at least co-authored, by Emily’s brother. He provides no proof for any of his claims.

Another Branwell champion was the Yorkshire poet Alice Law, who published her study titled Patrick Branwell Brontë in 1923. Whereas Gaskell elevated Charlotte by diminishing Branwell, Law defended Branwell by denigrating Charlotte. Law trots out theory after theory for Branwell’s authorship of Wuthering Heights, including the novels “masculine tone,” but she offers no concrete evidence.

Daphne Du Maurier, whose The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë was published in 1960, attributed partial authorship to Branwell. Du Maurier claimed that Branwell and Emily could have written together, but her theory rests on the same muddy arguments as the others, Johan said.

|

| Johan Hellinx |

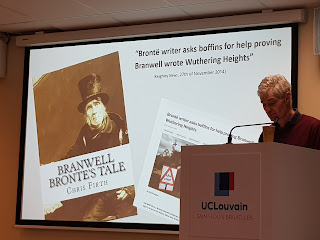

In 2014, the author Chris Firth raised the discussion about Branwell’s authorship again, based on the same arguments used by Alice Law in 1923. Firth called for a computer analysis to determine who is the true author of Wuthering Heights. The analysis was subsequently performed.

The final verdict: “If anything, our results show that Branwell is the least likely member of the Brontë family to have contributed to Wuthering Heights.”

While Johan concluded that the evidence clearly points to Emily’s authorship, the debate is sure to go on – and no doubt accompanied by more fake news.

No comments:

Post a Comment