Have you ever looked in the mirror and seen one of your parents or grandparents? Or maybe you have glimpsed a stranger, who seemed oddly familiar, and realised that you were looking at a reflection of yourself in a plate-glass window? Such experiences can be oddly unsettling. They suggest we are not “quite with it” – and maybe are starting to lose our grip on reality.

Gothic

novels exploit such moments, along with ghosts and other supernatural events,

to undermine rational thought. “Walls between the past and the present … [and]

the living and the dead” break down in Gothic fiction, according to Simon

Marsden, a senior lecturer at the University of Liverpool.

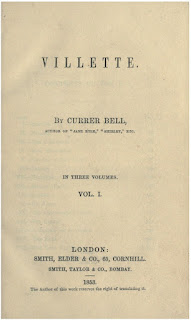

In his recent talk to the Brussels Brontë Group, In the Dead of Night, I Suddenly Awoke – The Gothic Mode of Villette, Dr Marsden argued that this sense of instability is inherent in Villette because Charlotte Brontë saw it as essential for conveying the experiences of her heroine, Lucy Snowe.

Charlotte had been experimenting with using features of Gothic novels in her writing since the age of 13, Dr Marsden said. Out of all of her books, Jane Eyre is the one most associated with the Gothic mode. Since its publication, it has inspired many writers, such as Henry James – author of what is often considered one of the most chilling stories of all time, The Turn of the Screw – as well as film-makers. Dr Marsden considered, however, that it was in Villette that Charlotte Brontë's use of Gothic elements “reached its full artistic fruition.”

The title of Dr Marsden’s talk came from a scene in chapter 8 of the novel. At that point, Lucy has arrived at the Pensionnat, has eaten some supper, and gone to bed, when she suddenly wakes up to find “a white figure stood in the room.” The figure turns out to be that of Madame Beck, who sits for a quarter of an hour on her bed “gazing” fixedly at Lucy, with a “face of stone.” There is a stark contrast between this image and the “human” and even “motherly” looks that Madame Beck had cast at Lucy earlier in the evening. Her white attire and marble face, stripped bare of humanity, combine to create a ghostly impression.

Gothic novels tended to have a number of common features such as a European setting, an isolated female protagonist, and a domestic tyrant. In Villette, these facets are represented respectively by the fictional kingdom of Labassecour (based on Belgium), Lucy Snowe and Madame Beck, or perhaps Paul Emanuel, a professor who often tyrannised his female pupils. Another common characteristic of Gothic novels is that while supernatural elements are frequently invoked, they are subsequently found to have rational explanations. Dr Marsden suggested that Charlotte Brontë was sometimes “poking fun” at the Gothic style; for example, the pensionnat, a former convent, is haunted by a ghost, who is finally revealed to be a young man visiting one of the pupils (Ginevra Fanshawe).

The use of Southern European Catholic countries as settings became increasingly common in English Gothic novels as Catholicism was associated with superstition. Gothic novels debunk ghosts and other supernatural occurrences in order to undermine such credulity. The use of Gothic elements, however, can go further in posing the question “of whether we can ever rid ourselves of ghosts.” When Lucy Snowe is recovering at La Terrace, the home of Mrs Bretton and her son Dr John Bretton, she glimpses in the mirror a "spectral" image of herself. She looks around from where she is lying on the sofa, and finds herself looking at furniture and objects “of past days, and of a distant country.” This mode of “Psychological Gothic” writing was used increasingly as the nineteenth century progressed. Freud was to later call this “the unhomely” or “uncanny,” meaning that the boundary between the familiar and the unfamiliar has broken down.

Dr Marsden noted that romantic poetry called on reason, and the need to respond emotionally and imaginatively to the natural world. He drew attention to an early passage in Villette in which a storm is raging. Lucy Snowe thinks “three times in the course of my life, events had taught me that these strange accents in the storm – this restless, hopeless cry – denote a coming state of atmosphere unpropitious to life.” She believes epidemics “were often heralded by a gasping, sobbing, tormented, long-lamenting east wind.” The text oscillates between vocabulary that is almost scientific and the string of dramatic adjectives used to describe the “cry” of the wind. This illustrates Charlotte Brontë’s romantic response to the storm. Her need for imagination rather than for being exclusively rationalist is reflected in her use of the Gothic mode to express the reality of Lucy’s life in Villette.

This was an inspiring talk, which opened up a new way of thinking about the novel, and about its place in 19th-century English literature. Gothic romances in the late 18th and early 19th centuries began with Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto published in 1764. It was Mrs Radcliffe, however, who is probably the most famous Gothic novelist, a fame possibly mainly attributable to Jane Austen’s satire of The Mysteries of Udolpho in Northanger Abbey. In her introduction to the Penguin Classics edition of Austen’s novel (1995 edition), Marilyn Butler, states that in Walpole’s novel and its immediate successors, the key features were “the cruel tyrant, and … his vast prison-like fortress as the setting for his crimes.” By contrast, she noted that Mrs Radcliffe “shifts the emphasis in significant ways.” Notably, “she diverts the reader’s attention … to the heightened and paranoid consciousness” of the female protagonist.

The heroine of Northanger Abbey is Catherine Morland, who is introduced to the reader as an atypical heroine, in that she has a happy family background in which her clergyman father “was not in the least addicted to locking up his daughters.” Despite this, Catherine does find herself somewhat isolated when she goes on a visit to Bath with Mrs Allen, a friend of the family. While there, she meets the vivacious Henry Tilney, who parodies Mrs Radcliffe as he drives her to stay as a guest at the Abbey, his family home. He asks Catherine “will not your heart sink beneath you” when you are led along “many gloomy passages … to a gloomy chamber, … the bed presenting even a funereal appearance,” and left to your own devices by a maid who “gives you reason to suppose that the part of the abbey you inhabit is undoubtedly haunted and … that you will not have a single domestic within call.” He then elaborates further on what might happen to Catherine during her stay, drawing on the usual events, which Butler summarised as the heroine exploring an unknown house in the dead of the night, “in fear of ghosts and whatever else she may find.” Nonetheless, “by mastering their fear and opting for rationality,” heroines overcome their childish fear of the dark, and mature into “self-reliance.”

It can be argued that this is exactly what happens to Lucy Snowe in Villette. She arrives at the Pensionnat, following a traumatic past, to live with unknown people, without friends, in an unknown city. The scene in which Madame Beck’s ghost-like figure appears in Lucy’s room ends with the sentence “All this was very un-English: truly, I was in a foreign land.” Lucy has crossed a boundary, which may lead her into all sorts of dangers. She has no choice, however, but to explore the unknown territory. She suffers repeatedly, and even has a sort of mental breakdown. Yet by the end of the novel, she has her own flourishing school, which the reader can imagine she will continue to run even without Monsieur Paul.

In the scene that gave Dr Marsden the title of his talk, the Gothic element is strangely invoked. Although the “figure in white” moves silently, we are instantly told that it is Madame Beck “in her night-dress,” which is hardly spine-tingling. What is disturbing, however, is that Madame watches Lucy for fifteen minutes, and even pulls up her night cap to get a better view of her, and Lucy never stirs. Anyone who has ever tried to feign sleep, whether as a child or adult, knows how hard it is to stay absolutely still; presumably, Lucy too had a “face of stone.” Furthermore, when Madame Beck leaves her room to take an imprint of her keys, Lucy states: “I softly rose in my bed and followed her with my eye.” The use of the word “softly,” which we would not usually associate with the activity of spying, and the phrase “followed her with my eye” rather than simply “I watched her” are both disquieting. By the end, Madame has taken stock of Lucy, but she is apparently unaware that Lucy has done likewise of her. The mutual observation and surveillance prefigure the relationship between the two women throughout the novel. Lucy may be alone and vulnerable in a foreign land, but she has shown an inner strength, albeit one of passive endurance.

Despite, Lucy’s calm exterior, she is a sensitive heroine, which is another characteristic of Gothic romances. Writing in the introduction to The Mysteries of Udolpho (Oxford World’s Classics, 1998), American academic and critic Terry Castle stated that Mrs Radcliffe “wished to reawaken in her readers a sense of the numinous – of invisible forces at work in the world,” as this sensibility had to some extent been lost with the Enlightenment. These were partly religious beliefs, but also as for Wordsworth and Blake, the effects of the imagination. Castle explained that “if ghosts … are resolutely excluded from the sphere of action, they reappear … in the visionary fancies of the novel’s exemplary characters.” In particular, ghosts of loved ones appear to those “of refined sentiment” and “with a feeling heart.” In this sense, Lucy is susceptible to both malign and good influences, but – like a typical Gothic romantic heroine – she is able to differentiate between them and make rational choices.

In Pleasure and Guilt on the Grand Tour, Travel writing and the imaginative geography 1600 – 1830, Chloe Chard explained that travellers sought to frame their experiences by using opposites to describe the familiar and the foreign. She noted that Gothic novels dramatized “the horrors of southern, Roman Catholic Europe” in opposition to “the restrained and discriminating exercises of the sentiments.” She cites The Mysteries of Udolpho for its “especially crisp distinction” between the “fierce and terrible passions” of the inhabitants of the castle, and the heroine’s “silent anguish, weeping, yet enduring.” Thus Gothic romances were, at least in part, reflecting the writing and experiences of early tourists. However, as Helen MacEwan noted during the discussion after Dr Marsden’s talk, Villette, is set in the heart of a city, and the Pensionnat may have once been a convent, but it is certainly not an old ruin in Italy.

Charlotte Brontë transposed the Gothic plot devices to her particular site of interest, the Pensionnat in Brussels, where she had studied and worked, and fallen in love with Monsieur Héger. Moreover, she depicted Lucy at times when she appeared to be losing her sense of reality, which played on the Gothic, but also incorporated contemporary concerns about the new and developing field of psychology. Dr Marsden called this “Psychological Gothic” – which sounds very close to sensation literature. Terry Castle quoted Henry James, who wrote that “To Mr Collins lies the credit of having introduced into fiction those most mysterious of mysteries, the mysteries that lie at our own door. This innovation … was fatal to Mrs Radcliffe and her everlasting castle in the Apennines.” In this sense, Villette, which was published in 1853 just six years before The Woman in White, interwove traditional features of Gothic novels with more contemporary ideas about the health of the mind.

George Elliot said of Villette that it was “almost preternatural” in its power to disturb its readers (quoted in the introduction to the Oxford World’s Classics edition, 2000). This quality may be due to the way in which Charlotte Brontë imaginatively reconstructed her own experiences in Brussels to create a heroine in the Gothic tradition, rather than use a simple realistic description that, as Dr Marsden showed, would have failed to accurately describe Lucy’s life.

Dawn Robey

No comments:

Post a Comment